כמעט, ואולי לגמרי, בלתי אפשרי להתעלם מהקשר התודעתי, הגורדי, שנוצר בין נוף לפוליטיקה. בהקשר המקומי הכוונה לסכסוך הישראלי ערבי: רבים מביטים כיום על יערות עצי המחט בהרי ירושלים, פאר מיפעלות הייעור של המוסדות הציוניים, בעין ביקורתית כניסיון להביא את אירופה למזרח ובפריזמה של הפרת האיזון האקולוגי המקומי; שיחי צבר הם לעולם סימון חורבות כפר פלשתיני.![IMG_4431[1]](https://www.smadarsheffi.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/IMG_44311.jpg)

לאופן ההתבוננות הזה יש מאין תאריך הולדת. ב 1993-94 יצר לארי אברמסון את סידרת tsooba, ציורים קטנים (25X25 ס”מ) בצבעי שמן. הנוף שצויר היה סביבות קיבוץ צובה על שרידי הכפר הערבי צובא, שהפכו, מכבר, לחלק מאתרי הטיול באזור. לציורים הצמיד מעיתון “חדשות” ואלו, ההטבעות על עיתון שמאל שנסגר כמעט במקביל לעשיית הסדרה, הפכו דיבור על נוף בארץ לפוליטי באופן בלתי נמנע. השאלה האם יש נקודות מתות בהתבוננות האמן, עיוורון כלפי נרטיב היסטורי, נהייתה אבן בוחן.*

ב 1994 ראה אור ספר המאמרים המשפיע של וו. ג’י. טי. מיטשל Landscape and Power ששרטט קו פוליטי ומאתגר לקריאת נוף. בספר, לצד התייחסות לנוף בניו זילנד ומלחמת המתיישבים הלבנים במאוריים, פוליטיקה של תכנון נוף בגנים בריטים וייצוגי נופים באפריקה, גם התייחסות לייצוגי נוף בישראל- פלשתין.

בהקדמה למהדורה השנייה, ב 2002 כתב מיטשל שהיה משנה את שם הספר ל landspace space, place and וכותב “Landscape exerts a subtle power over people eliciting a broad range of emotions and meanings that may be difficult to specify . מיטשל ממשיך ומסביר את החלוקות וההבדלים בין חלל (הפחות מוגדר) למקום (שיש בו בעלות) וגם בוחן מתי “חלל” או “מקום” הופכים ל”נוף”. בהקשר זה מעניין לחשוב על הקונספט היהודי של “מקום” כמאחד פיזי ומטאפיזי.

תערוכה זו פועלת בשדה “טווח רגשות ומשמעויות שקשה להגדיר”, כפי שניסח זאת מיטשל. genius loci היה בדת הרומית הכינוי לרוח שהגנה על מקום. כיום משתמשים במונח הלטיני “רוח המקום” במובן של תמצית, אם נרצה הנשמה היתרה. העבודות ב genius loci אינן מניפסטים אך הן פועלות בתוך העולם. הן נוגעות בדק מן הדק, בשקט שבין תווים, אינן מתייחסות בהכרח לנוף ספציפי אך בהחלט ל”מקום”.

***

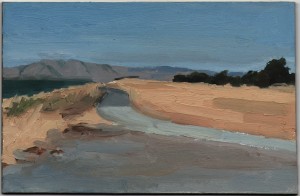

אלינור ריי האמריקאית תופסת בציוריה הקטנים מרחבי אין סוף, את התחושה של מלוא העין. הדיוק, האומץ בהנחת הצבעים, בונים מערך שדומה שלא יכול היה להיות נכון ממנו. נופי מים ונוף שדה עומדים בבטחה ושלווה, גולשים מעבר למה שהמבט מכיל.

בשדות של מוש קאשי מולך ריק כאילו היו שלב היולי של בריאה, לפני השלמת ששת ימי המעשה, אך אחרי ההפרדה למים והשמים, לתחתונים ולעליונים. המבט מרחף בעבודות וחוגג את הריק, את ההווה שנוכח בהם כאילו הוא בלתי משתנה.

הציור של יהודה ארמוני שבקדמתו ערמת חציר מתערסל בזרועות הזיכרון האמנותי, זה שבין “המלקטות” ,1857 של מילה ( Jean-François Millet) לערמות החציר של מונה 1890-91 (Claude Monet ). הדשנות של הציורים ההם, של מאה אחרת ומקום אחר היא שכבה שקטה של משמעות במקום ששממה מזנבת בקצותיו.

העבודות של אורי בלייר,טלי נבון והדר גד נוגעות בכאן הישראלי, אבל אינן מוגבלות בו.

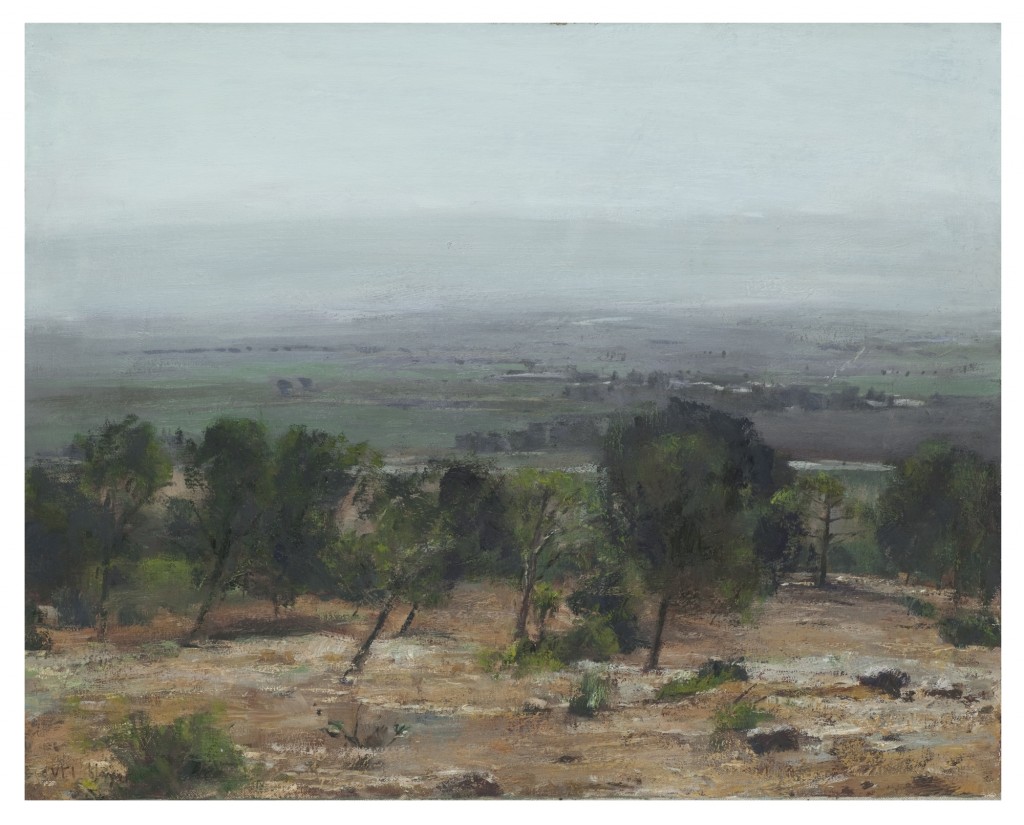

“עמק אפור” של אורי בלייר הוא עמק החולה שהוא חלק מהמיתוס הלאומי-ציוני: העיר ברקע היא קריית שמונה הקרויה על שם הרוגי קרבות תל-חי. ימת החולה, האתר המרכזי בעמק, יובשה בשנות ה 50 כפרויקט לאומי שנתפס כהפעלת אמצעים מודרניים על מנת להכפיף טבע לטובת האדם. הייבוש שינה דרמטית את האיזון האקולוגי ואת ה genius loci. בשנות ה 90, בתהליך מלאכותי החיו חלק מהימה ויצרו אתר שחשיבותו הסימבולית רבה, כמסמן שינוי בחשיבה הישראלית על נושאים סביבתיים ועל מגבלות השימוש בכוח. הציור של בלייר אמביוולנטי ואניגמאטי,מכיל את זיכרון הפגיעה והמזור החלקי.

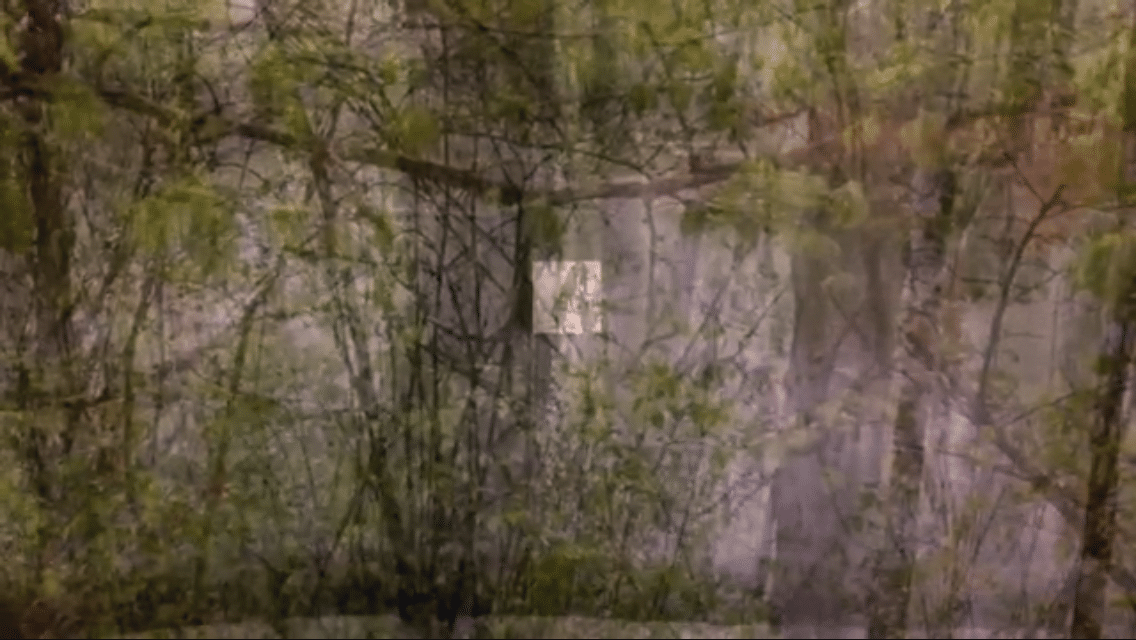

בוידיאו של טלי נבון קולאז’ דימויים, הצטלבות משאת נפש של טבע אידיאלי עם מבט בכיכר הבימה (תכנן דני קרוון). הכיכר היא חלל הממלכתי באופיו, לבנה, בוהקת, חשופה. הטבע הפך בה לנוסטלגיה לא ממוענת, זיכרון נופים שבינוי מאיים על רובם. הדימויים המרובדים רכים אבל התחושה של שיבוש עמוקה. מתחת לכיכר מצויים מרחב מוגן ומקלט רחבי ידיים, מבנים הכרחיים, חללים נסתרים מהעין שמשקפים את האי שקט התת קרקעי המפעפע במציאות השלווה, הבוטחת לכאורה.

זווית מפגש של צינורות השקיה, קרקע חשופה, ערמות עלים, ושרכים המטפסים על ברושים הם מרכיבי הנוף בציור בית הקברות של הדר גד. המקום, בית קברות של קיבוץ עין –חרוד, אתר קדושה חילוני, צופן מרכיבי נוף מקומיים: צינורות ההשקיה, ניסיון שליטה בלתי מוסתרת בטבע, ולמרות זאת הצחיחות, תזכורת למאמץ התמידי שנדרש לדחיקתה.

סטיוארט שילס, אמריקאי, מצייר את מה שנקלט בהרף עין ונטבע בזיכרון. אין ספור גווני ירוק משתקפים במים שבהם אדווה כמעט בלתי מורגשת. המראה מלא, מה שיכל להיות רפלקציה איננו כזה. שילס מצייר מהתבוננות אך הישות שנוצרת, האובייקט, אינו מה שאריסטו כינה “מימזיס”. הוא מקבע את החמקמק והקיים, מנכיח את רוח המקום.

אין הפוגה ממסרי ההיסטוריה הקרובה, מהתרחשויות ההווה, הפוליטיות והאקולוגיות. במחשבה רומנטית אפשר לחשוב על כך שכאשר יעלו הפצעים בנוף ארוכה הם יהיו לשכבות בזיכרון של רוח מקום.

*כפרים חרבים צוירו בשנים המוקדמות למדינה וחזרו והופיעו בספרות ושירה כתיעוד והנצחה. הפעולה של אברמסון הייתה מהלך שונה כאשר הנכיחה את העיוורון שהתפתח ופשה במבט הישראלי, המהירות בה הפכו חורבות ממצבת כאב למבנים רומנטיים או שקופים.

רשמה לניוזלטר הפירסומי השבועי של “החלון” בנושאי אמנות, אירועים ותערוכות חדשות – www.smadarsheffi.com/?p=925 (הרישום נפרד מהרישום לבלוג )

Genius Loci

It is nearly impossible to ignore the inextricable tie that binds landscape and politics. In the local context, this usually refers to the Israeli-Arab conflict. The pine forests in the Jerusalem hills, the glory of the Zionist national institutions’ afforestation projects, are often viewed as an attempt to Europeanize the East and as a disruption of the local ecosystem’s balance. Sabra cactus hedges are forever read as demarcating ruined Palestinian villages.

This mode of observation came to the fore in 1993-94 with Larry Abramson’s “Tsooba” series of small oil paintings (25x25cm) of the landscape around Kibbutz Tzuba, encompassing the ruins of the Arab village of Tzoba, now part of the hiking route in the area. He pressed newspaper pages from Hadashot, a leftist daily (closed down around that time) onto the surface of the canvases, then peeled them off. The series generated a discourse on the inevitable politicization of the Israeli landscape. The issue of blind spots in the gaze has become a litmus test of an artist’s moral stance. (In the early years of statehood, painters depicted Arab villages as documentation and commemoration. What Abramson did was to make present the blindness that became part of the Israeli gaze and the rapidity with which ruins were transformed from a monument to pain into romantic or transparent structures).

W.J.T. Mitchell published his influential book Landscape and Power in 1994. The essays delineated a challenging political line of thought on reading landscape. Along with articles on the New Zealand landscape and the white settlers’ war against the Maori, the politics of British garden landscaping and representations of African landscapes, Mitchell also referred to representations of landscape in Israel-Palestine.

In the Introduction to the second edition (2002), Mitchell wrote that he would have changed the title to Space, Place and Landscape: “Landscape exerts a subtle power over people, eliciting a broad range of emotions and meanings that may be difficult to specify.” Mitchell explains the differences and divisions between space (less defined) and place (which has ownership), and examines when “space” or “place” becomes “landscape.” In this context we may note the Hebrew word “makom,” used to refer to both locale and the Omnipotent.

The current exhibition lies in the field of what Mitchell has formulated as “a range of emotions and meanings…” The genius loci in classical Roman religion refers to the protective spirit of the place; in contemporary usage, the Latin expression which formerly meant “local deity” now refers to the essence or soul of a place. The artworks in the exhibition genius loci are not manifestos, but they do act in the world. They operate in the silence between notes, not necessarily referring to a specific landscape, but indeed to a place.

***

Eleanor Ray is an American painter who captures infinite expanses in her small-scale paintings, which fill the eye. Her exquisite precision and bold placement of colors create a system in perfect equilibrium. Waterscapes and a field face viewers confidently and calmly, overflowing what is contained in the viewer’s gaze.

2015

The void dominates Mosh Kashi’s fields, as if their moment were that of an early stage of creation after the primordial waters were separated into heavens and seas. The gaze hovers over the works and celebrates the immutable presence of their emptiness.

The haystack in the foreground of Yehuda Armoni’s painting is cradled in art historical memory, between Jean-François Millet’s The Gleaners (1857) and Claude Monet’s Haystacks (1890-91). The richness of the paintings from a different century and a different locale adds a subtle layer of meaning in a place where the constant threat of desertification lurks.

Works by Uri Blayer, Tali Navon and Hadar Gad touch upon, but are not limited to the Israeli present. “Grey Valley” by Blayer depicts the Huleh Valley, a place steeped in the Zionist national myth; the city seen in the background is Kiryat Shmona, named for the eight who fell in the battles for Tel Hai. The Huleh swamp was drained in the 1950s as a national project, regarded as a modern bettering of the land that dramatically altered the ecological balance and the genius loci. Part of the swamp was revived in the ‘90s in an artificial process, creating a site whose symbolic importance marked a pivotal moment in the Israeli attitude to environmental issues and to the exercising of power. Blayer’s painting is both ambivalent and enigmatic, containing the present as well as the memory of the past, wound and balm.

Tali Navon’s video is a collage of images, the yearning for an ideal Nature crossed with a look at Habima Square in Tel Aviv (designed by Dani Karavan). The square has an official state character, blazing white, exposed and barren. Nature in the square is but a nostalgic memory, out of context: it is a landscaped garden shaped as a memory of open spaces now threatened by construction. The layered images in the video are imbued with a deep feeling of disruption. Underneath Habima Square is a protective security space and a spacious bomb shelter, structures required by law, concealed spaces forming an underground asylum seeping into the seemingly safe reality above.

Hadar Gad’s painting of Kibbutz Ein Harod’s cemetery encodes local landscape elements. In her painting of this secular pilgrimage site, she works with the angle of encounter between irrigation pipes, exposed ground, heaps of leaves and foliage climbing up cypresses. The attempt to control Nature is blunt, yet the aridity is a constant reminder of the effort required to keep drought at bay.

American artist Stuart Shils paints what is perceived in the blink of an eye and stamped in one’s memory. Infinite shades of green are reflected in the water with an almost imperceptible ripple. The reflection of what may be a tree or a thicket is not refracted. Shils paints from observation, but the resulting entity, the object, is not formed from what Aristotle called “mimesis.” Instead, Shils makes the elusive permanent, consolidating the spirit of the place, making it present.

There is no refuge from recent history and current political and ecological events. Romanticism would have us believe that when the wounds in the local landscape heal, they will become layers of memory in the local spirit of the place.

Translation: J Appleton

Join the mailing list for Window’s weekly informational advertising newsletter –

www.smadarsheffi.com/?p=925

Comments – please write to thewindowartsite@gmail.com